|

| |

Issue no. 9 - May 1982

pdf

version of this Issue version of this Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

updated: 23 April, 2014

Pages 1-8 Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 9 - May

1982

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 9 May 1982  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

An integrated approach

Diarrhoea has diminished in the western world through public health measures which

ensure safer drinking water, better sanitation and improved food handling. Education has

brought greater awareness of the dangers of inadequate hygiene - both personal and

environmental. Such benefits have yet to reach many parts of the world.

|

Better

understanding about diarrhoea at all levels. Rehydration therapy alone is not enough. Getting fluids into people, especially

children, early enough will save lives but will not stop diarrhoea recurring unless the

causes of the problem are looked for and dealt with appropriately. There could be some

risk of complacency now that oral rehydration therapy is becoming more widely accepted as

the most effective immediate treatment and death rates from diarrhoeal diseases may be

being seen to decline. We cannot afford any such complacency because we still do not know

nearly enough about the longer term health effects of repeated attacks of diarrhoea. Diarrhoea Dialogue 10 will focus on chronic diarrhoea (see also page two of this issue).

|

|

Sharing knowledge is important

| Only a fully integrated approach can bring about well planned and

effective diarrhoeal disease control programmes. A vital part of such an approach is

communication. Better understanding about every aspect of diarrhoeal disease is needed at

all levels - from ministries of health down to semi-literate community workers. On pages four and five we consider practical ways in which

this crucial information gap can be more effectively filled. |

|

Marking an anniversary

With this ninth newsletter we reach Diarrhoea Dialogue's second birthday.

Previous issues have stressed a range of themes - including the importance of safe water

and better sanitation; oral rehydration therapy; health education and nutritional needs -

but with varying emphasis each time. All these aspects of diarrhoeal disease prevention

and control are significant and we have tried to supply factual information for people to

use in their own situations. Best of DD

Collections of items from earlier issues of Diarrhoea Dialogue are now being

produced. The first, which contains material from issues one to four, is available now.

Subsequent editions will appear annually. We hope this will help the many people who still

ask for back issues (many of which are out of print) and also provide a basis for more

translations. Keeping up the dialogue

Although it is only possible to publish a very few of your letters, we depend a great

deal on readers' response to alert us to the practical implications of diarrhoeal disease

programmes in the community (see Dr Gilbert Bukenya's letter on="#page3">page

three) and these, after all, are what really matter. K.M.E. and W.A.M.C.

|

In this issue. . .

- Oral rehydration therapy in Uganda

- Information and diarrhoeal disease control

- Haiti: carrying out a community survey

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 9 May 1982  1

Page 2 3 1

Page 2 3

Symposium on chronic diarrhoea Diarrhoea was as great a danger among children of the poor in Britain seventy years ago

as it continues to be among Third World children. At that time Professor Leonard Parsons

pioneered research in paediatric gastroenterology at the Institute of Child Health in

Birmingham where a one-day symposium in his memory was held in March, 1982. Among those taking part were paediatricians from overseas attending a course sponsored

by the British Council. Participants discussed many of the different factors which may

contribute to the vicious cycle of chronic diarrhoeal disease: dysfunctions of the small

intestine; the role of various infections, including parasites; malnutrition as both a

cause and an effect; the influence of deficiencies of certain trace metals, particularly

zinc; specific food intolerance's; pancreatic and gastric disturbances; effects on immune

function; and predisposition through a possible interplay between genes, diet and

environmental circumstances. Problems of differential diagnosis and choice of appropriate

therapies were explored. A thought-stimulating finish to the symposium was provided by Dr Jon E. Rohde's Leonard

Parsons Memorial Lecture on 'Why the other half dies: science and politics of child

mortality in the third world'. The proceedings of the meeting, which will include Dr

Rohde's lecture, are being edited by Professor A. S. McNeish and will be published by the

University of Birmingham. Promoting ORT in Nicaragua

"In 1979, there were only three centres in Nicaragua where children could receive

oral rehydration. With the help of WHO and UNICEF 289 oral rehydration therapy units have

now been installed in health centres all over the country. Community participation,

coordinated by the mass organizations set up by the Sandinista government, has played a

vital role in the promotion of ORT. During 1980-1981 more than 170,000 children under five

attended oral rehydration units. Over 50 per cent were fully rehydrated in the units, 41

per cent received further oral rehydration therapy at home and 2-5 per cent needed

intravenous treatment.

|

Mothers and children at an oral rehydration therapy unit in Nicaragua.

Only children with low to moderate dehydration required treatment during this period at

the units. This indicated that more mothers were using ORT early enough at home to prevent

serious dehydration. Reported death rates from diarrhoeal diseases have dropped

dramatically. The oral rehydration programme has been widely publicized in Nicaragua in schools,

through radio and television programmes, posters and leaflets, etc. During the literacy

campaign, more than. 200,000 'young brigadistas' took sachets of oral rehydration salts

(ORS) into rural areas making sure that information about treating diarrhoea reached even

the most remote parts of the country.

|

|

As a result of all these efforts, diarrhoea is no longer the major cause of infant

deaths in Nicaragua. The precise extent of the impact of the ORT programme on infant

mortality rates is being assessed by the Ministry of Health this year." Dra. Blanca Hernandez The AHRTAG baby length measurer

|

Using the baby length measurer

Regular measuring of babies and small children is a vital part of the monitoring of

infant growth and development. On behalf of the Nutrition Unit of the World Health

Organization, AHRTAG has developed a simple baby length measurer made from wood, which can

be taken apart for easy transport.

|

Prototype measurers are being tested in India and Colombia and initial reactions to

them from both mothers and health workers are very encouraging. Working drawings to make

the measurers are available from AHRTAG, 85, Marylebone High Street, London W1M 3DE,

United Kingdom.

|

In the next issue...

- We look at the particular problems of dealing with chronic diarrhoea

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 9 May 1982  2

Page 3 4 2

Page 3 4

Involving mothers

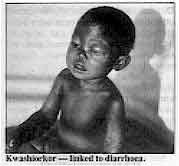

" Diarrhoeal diseases are a major health

problem in Uganda, causing high rates of infant mortality and contributing to

malnutrition. Rehydration is still carried out only by intravenous therapy in many

hospitals but attempts are being made to spread information about early oral rehydration

therapy (ORT). One such programme was started at the Kasangati Health Centre which is attached to

Makerere University Medical School, Kampala. The aim of the programme was to educate as

many mothers as possible in the hope that they would pass on the message to others.

Intensive efforts were made to train both medical and paramedical staff in the use of ORT.

|

Kwashiorkor - linked to diarrhoea. The assistant health visitors, who came from the same community and formed the core of

primary health workers, received particular attention. They were taught how to recognize

the signs of dehydration and simple preventive measures. The emphasis, however, was on

oral rehydration which is life-saving if started early.

|

All round enthusiasm

Confidence in ORT grew because of the enthusiastic involvement of teachers like the

late Professor L. Musoke, who vigorously demonstrated ORT to mothers in the wards during

community health education sessions. This had a big impact on mothers who became quite

confident in the method. The demonstration not only benefited the mothers but also another very important target

group - the junior doctors and medical students. They realized the value of the mothers'

participation and the need for their own involvement in practical demonstrations. Simple explanation

Diarrhoea was explained to the mothers in terms they could understand. Emphasis was

placed on the advantages of early ORT, recognition of serious symptoms and simple hygienic

measures that could realistically be carried out at home. These included washing hands

after using the toilet and before handling food, cleaning kitchen utensils and preventing

contamination of stored food. The six main points were:

- Start ORT as soon as diarrhoea is recognized and give one mug or glass (200ml) of oral

rehydration fluid for every stool passed (half a mug for a small child, and two mugs for

large children and adults).

- Do not stop breastfeeding. Breast milk is the best fluid and nourishment.

- Continue to feed the child as soon as initial rehydration is complete.

- If diarrhoea continues after two days of vigorous oral rehydration, or if the child's

condition gets worse, report to the nearest medical post or to the health centre.

- Do not buy any medicines for acute watery diarrhoea from shops or market places.

- If you have no sugar or salt, give clean or boiled water or fruit juices; these are

better than nothing.

|

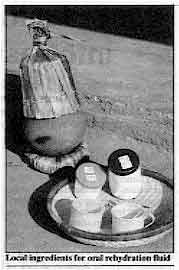

Local

ingredients for oral rehydration fluid

Mothers were taught by demonstration how to prepare oral rehydration fluids from

locally available materials and how to give the fluids to their children. The slogan was -

"Add two teaspoonfuls of sugar and a pinch of salt to a mug or glass of boiled water

(cooled). Always taste it before giving it to the child. It should not taste more

salty than tears*. Participation, rather than isolating mothers from the treatment of their own children,

was the key to the success of the programme. Cases of severe dehydration decreased within

the area and it is one place in Uganda where mothers immediately start oral rehydration as

soon as a child has diarrhoea.

|

|

Conclusion During the political upheavals of the late 1970's in Uganda it was almost impossible to

maintain even this basic ORT programme. However, now that salt, sugar and mugs are again

available the ORT programme is being promoted to reduce the need for widespread

intravenous rehydration in hospitals. Oral rehydration therapy can be made available

cheaply for many children whereas intravenous therapy is time-consuming and only available

to a tiny minority. It places an unnecessary extra burden on the health budgets of

countries with limited resources such as Uganda." Dr Gilbert Bukenya * At this time ORS packets were not available in Uganda. The recommended simple

formula for oral rehydration solution is one level 5ml teaspoonful of salt plus eight

level 5ml teaspoonfuls of sugar mixed in one litre of drinking water.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 9 May 1982  3

Page 4 5 3

Page 4 5

| Better communication about diarrhoeal diseases |

Filling the information gap

Poor understanding about diarrhoea does not stop at the village boundary. There is

a need for increased information about diarrhoeal disease prevention and control at all

levels. We consider some ways in which this could be achieved. A frequent complaint from readers to Diarrhoea Dialogue over the past two years

concerns the lack of other information about diarrhoeal disease prevention and control.

Many people - whether at local or national level - are unaware of information and help

that may already be available. For example, middle level health workers may despair of

being able to develop teaching materials because of lack of resources, when assistance

could be found if they knew where to look for it. At national level, staff within health ministries may be interested in starting a

national diarrhoeal disease control programme and wonder how to do this. Perhaps they are

unaware that the World Health Organization (WHO) runs training courses specifically to

train national programme managers. What information?

In the first eight issues of Diarrhoea Dialogue we have focused on a wide

range of topics including:

- oral rehydration therapy

- mothers' attitudes to diarrhoea

- health education and diarrhoea

- environmental health

- diarrhoea and nutrition

- aetiology

- drug therapy

There is no shortage of information on most aspects of these topics but it is either:

- not reaching the people who most need it

or

- reaching them in a poorly presented way that is difficult to understand.

Therefore, through no fault of their own, people may not understand why it is important

to:

- give oral rehydration therapy as soon as diarrhoea starts

- continue to breastfeed children with diarrhoea

- keep faeces away from drinking water

- handle all foods with care - especially weaning foods.

Emphasising key points

People obviously need to be kept in touch with new developments in the diarrhoea field

- but we should remember that much existing useful information still has to be adequately

circulated. This is one of the main reasons why Diarrhoea Dialogue was started, so

that as well as providing updates on research, it could also serve this purpose. There are key areas where information is still very scarce. Certainly, not enough

information exists that actually puts diarrhoeal diseases into an overall context rather

than just considering single aspects of the problem. Another area which needs to be

developed is how to find out what community attitudes are to diarrhoea so that more

appropriate programmes can be developed. We consider simple survey techniques on pages="#page6">six and seven of this issue. Which levels?

People need to know whom they can contact both within their own country and outside, if

necessary, either to obtain information or to develop their own materials. Interest must

be stimulated at a central level so that requests from other parts of the country for help

in developing materials can be responded to. How might this approach work at different levels? Internationally: organizations such as WHO, UNICEF, the International Centre for

Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B) and the Ross Institute of Tropical

Hygiene (see full listing="#Some">below) can offer help in a variety of ways.

For example:

- As mentioned above, WHO runs training courses for national diarrhoeal disease control

programme managers, and supports and encourages proposals for field and operational

research that will lead to more information about aspects of diarrhoeal diseases in the

community.

- The Ross Institute will shortly be publishing two wall charts (one aimed at senior and

the other at middle level health staff) which give 'at a glance' information about the

causes of diarrhoea, therapy, transmission routes, epidemiology and control measures etc.

We will include more details about the charts in Diarrhoea Dialogue

10.

- UNICEF's Project Support Communications (PSC) staff in their country offices can help

with the organization of workshops on the development and production of health education

materials.

Nationally: managers of national diarrhoeal disease control programmes, senior

paediatricians and public health staff need to promote the importance of information on

all aspects of diarrhoeal disease control. They can pass on the key messages themselves

when teaching people at district level. District: middle level staff can spread information down to community level

through training. They can adapt to local conditions more general national suggestions for

diarrhoeal disease control programmes. This information exchange between the different levels must be two-way and regular.

Staff in charge of planning programmes at national level must have regular input from all

parts of the country to be able to run a diarrhoeal disease control programme effectively.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 9 May 1982  4

Page 5 6 4

Page 5 6

| Better communication about diarrhoeal diseases |

What presentation?

If information/training programmes are aimed only at local people this will have little

effect in the long term. Middle and senior level health staff must also be involved.

Obviously materials appropriate for use by senior level staff need a different

presentation. Nevertheless, the messages conveyed may not be that different. Poor

understanding about diarrhoeal disease control and prevention does not stop at the village

level. On the contrary, it is often found throughout the health infrastructure. Wherever

health staff are being trained, there should be consistent information about diarrhoeal

diseases. This may seem an obvious requirement given the high infant mortality rates

caused by diarrhoeal diseases in many countries, but it still does not happen in many

places. There are various useful formats for presenting information depending on the level of

the target audience and whether the material is to be used for teaching or general

information. To list a few:

| Audio-visual |

Publications |

Traditional methods |

Films

Slide sets

Video tapes

Radio

Television |

Newsletters

Local newspapers

Calendars

Posters

Flashcards

Cartoons

Comics |

Theatre

Puppets

Storytelling

Songs |

The organizations listed on this page may be able to give you

suggestions about developing these and other materials. Diarrhoea Dialogue

Over the past two years, Diarrhoea Dialogue has tried to fill part of the

information gap. The newsletter is aimed at a very broad audience (we now send English

copies to over 12,000 individuals and organizations in 95 countries and also have French

and Spanish editions which reach a further 9,000 people). Although this means that

we can never satisfy everyone all of the time, the advantage is that many people who would

otherwise receive no information at all can now expect something regularly. It also means

that we receive a wide range of information from you. Many of the ideas in Diarrhoea

Dialogue are now contributed by readers so the publication has developed into the

two-way dialogue that was always intended. Our readership reflects the principles put forward in this article in that it includes

health staff working at all levels. We hope that some of you reading this may be able to

use the information given here to increase awareness about diarrhoeal diseases in your

village, district or country. Please share your views and experiences with other readers

through Diarrhoea Dialogue. Denise Ayres

Some of the organizations involved in the spread of information

on diarrhoeal diseases:

- Appropriate Health Resources and Technologies Action Group Ltd

85 Marylebone High Street

London W1M 3DE

United Kingdom

- Diarrhoeal Diseases Control Programme

World Health Organization

1211 Geneva 27

Switzerland

- International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh

PO Box 128

Dacca 2

Bangladesh

- International Childrens Centre

Chateau de Longchamp

Carrefour de Longchamp

Bois de Boulogne

75016 Paris

France

- International Development Research Centre

PO Box 8500

Ottawa

Canada K1G 3H9

- Ross Institute of Tropical Hygiene

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Keppel Street

London WC1E 7HT

United Kingdom

- Water and Environmental Sanitation Team

Programme Development and Planning Division

UNICEF

866 UN Plaza, Room A415

New York, NY 10017

USA

- Water and Sanitation for Health Project

1611 N. Kent Street

Room 1002

Arlington Virginia 22209

USA

Other sources of information on development of health education materials:

- British Council Media Group

10 Spring Gardens

London SW1A 2BN

United Kingdom

- British Life Assurance Trust Centre for Health and Medical Education

BMA House, Tavistock Square

London WC1H 9JP

United Kingdom

- Bureau d' Etudes et de Recherches pour la promotion de la Sante

B. P. 1977

Kangu-Mayombe

Zaire

- PIACT de Mexico

Shakespeare No. 27

Mexico 5, DF

Mexico

- Teaching Aids at Low Cost

Tropical Child Health Unit

Institute of Child Health

30 Guilford Street

London WC1N 1EH

United Kingdom

- UNICEF

Development Education Officer

Office for Europe

Palais des Nations

1211 Geneva 10

Switzerland

- Voluntary Health Association of India

C-14 Community Centre

Safdarjung Development Area

New Delhi 110 016

India

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 9 May 1982  5

Page 6 7 5

Page 6 7

| Practical advice series: gathering information in the

community |

Carrying out a survey on attitudes to

diarrhoea

Mothers' attitudes are critical to the success of ORT programmes. A survey to find

out their beliefs should, therefore, be an essential step before developing a programme(1,2). We recently received a study from Haiti offering practical suggestions on gathering

information before starting a national oral rehydration therapy programme. The study was

begun in late 1981. For a year before then, Haiti had been implementing a hospital based

ORT programme (3). Although attempts had been made to teach mothers about the use of oral

rehydration solution for several years, community and home-based approaches to oral

rehydration therapy were still new ideas. The Research Section of the Division of Family Hygiene, Department of Public Health and

Population discussed the situation with public health workers and drew up a list of simple

questions to ask mothers. The questions were designed to give insight into attitudes to

diarrhoea in the community and mothers' beliefs about its cause and cure. The questions

included:

- How do you know when your child has diarrhoea?

- What causes it? What other names do people use for diarrhoea?

- Is diarrhoea a disease? Can a child die from it?

- Do you know a child who has died from diarrhoea?

- What do you do when your child gets diarrhoea?

- Should liquids and/or food be given when your child has diarrhoea?

- Why or why not?

- What are good foods/liquids for a child who has diarrhoea?

- Should you continue breastfeeding a child who has diarrhoea?

- Who in your community can help you if your child has diarrhoea? (doctor, health worker,

traditional birth attendant, leaf doctor, traditional healer, etc.)

- Is there a particular medicine you give your child when he has diarrhoea? Which one?

- Would you like to learn how to treat diarrhoea with a solution of salt and sugar which

you can make in your home?

Survey in urban areas

|

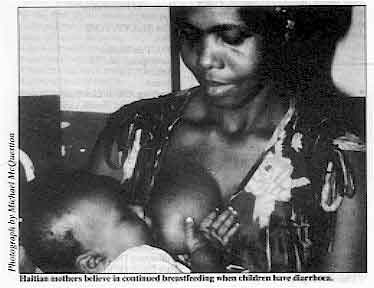

Haitian mothers believe in continued breastfeeding when

children have diarrhoea. These questions were translated into Haitian Creole and posed initially to half a dozen

mothers living in or near the capital city. These mothers had already heard of ORT, knew

about mixing a home-made solution of sugar and salt, believed strongly in continuing

breastfeeding, giving liquids (boiled and carefully handled), and spoke of reducing heavy,

fat foods but not eliminating food altogether. The families were also aware of the danger

of dehydration from diarrhoea and knew they were dealing with a potentially serious health

problem. They generally recommended seeing a doctor and knew specific health facilities

where they could get help.

|

While the first interviews also provided ideas on foods and liquids that are

traditionally considered good and bad in treating diarrhoea (diarrhoea is considered to be

a "hot" illness in Haiti so "cool" foods must be given), the mothers

had obviously already had some exposure to modern ideas. Rural areas

Consequently, the next interviews were with mothers in more isolated rural areas. A

total of 16 interviews lasting between 10-30 minutes were taped. Rather than transcribing

all the data, the cassettes were replayed several times and notes taken on the most

relevant points. The fieldwork in five different rural areas was done by the Haitian

Center for Applied Linguistics, which was gathering data for a linguistic atlas of Haiti

and offered to cooperate with the Division of Family Hygiene's Research Section. The age of the respondents varied between 20 and 70 years. All the women interviewed

recognized diarrhoea by the presence of liquid stools in great quantity and most saw it as

a life-threatening disease. The majority said that food intake should not be stopped

during diarrhoea, and generally had reasonable ideas of the type and quantity of food to

provide. The general consensus was that breastfeeding should continue in order to give the child

strength and that liquids (tea, juice, rice water, cow's milk) should continue as well.

Half of the respondents had already heard of ORT. The causes of diarrhoea mentioned included teething and 'spoiled' mother's milk as well

as some modern beliefs related to poor hygiene. Treatment of diarrhoea begins at home but

many of the mothers mentioned the need to seek medical assistance. Results

The main results of this small study were confirmed in a larger nutrition survey of

almost 900 mothers which included questions about their views on the nature of diarrhoea,

and feeding practices to follow when it occurs. This supported a general feeling that

mothers in rural Haiti are very favourable to the introduction of an ORT programme. There

do not appear to be traditional attitudes and beliefs that are obstacles to a national

effort to treat diarrhoea. Mothers seem to be quite ready to take action when diarrhoea

strikes and are ready to accept an appropriate technology. In Haiti a complex magico-religious system underlies views of health and illness and

what can be done to resolve problems. While a simple study focusing on practical issues in

ORT did not need to analyse this system in detail, a sympathetic awareness of the

importance of traditional medicine (often all that people in rural areas have to help them

in major crises) is very important. The team who carried out the study described here plan

further work on this subject. Study sent by Dr James Allman, Center for Population and Family Health, Columbia

University and Dr Maryse B. Pierre-Louis, Division of Family Hygiene, Department of Public

Health and Population, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. (1) Rohde J E 1980 Attitudes and Beliefs About Diarrhoea: The Mother's Role. Diarrhoea Dialogue 2: 4-5

(2) Lozoff B, Kamath K R and Feldman R A 1975 Infection and Disease in South Indian

Families: Beliefs About Childhood Diarrhoea. Human Organization Vol 34, No. 4: 353-358

(3)Pape J 1981 Introduction and Promotion of Oral Rehydration Fluids in Haiti.

USAID, Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 9 May 1982  6

Page 7 8 6

Page 7 8

| Practical advice series: gathering information in the

community |

General points to remember:

Many people dislike or distrust surveys. This is particularly true in poor

communities which are frequently studied but rarely see any results. Proper organization

of a survey and a sympathetic approach when carrying it out will make it far more likely

that the end results will be acted upon.

- Try to find out what problems people feel are most important and see what ideas they have

for solving them.

- Only ask for the minimum amount of information necessary for the survey.

Make sure that people understand why you are collecting the information.

- Talk to enough people to ensure collection of a cross-section of opinion from within the

community. The number of people you can reach will obviously depend on the questioners

available. If you are training questioners, it is very important to spend

time on this. An unsympathetic, abrupt approach when asking questions can produce forced

answers and ruin a survey.

- Try to ask questions in such a way that people can learn something at the same time as

they answer. Avoid asking leading questions and if a person does not understand what to

reply, offer several different possibilities including an open response like 'none of

these answers'.

- If possible, try to avoid using questionnaires when talking to people (small tape

recorders were used in the Haiti study).

However, you will need questionnaires/checklists at some stage to set down the

information gathered in a logical way. Apart from the questions listed on="#page6">page

six, the following topics could also be included in a diarrhoea survey:

- What household remedies are available for diarrhoea?

- Does each household have a supply of salt and sugar which could be used for making oral

rehydration mixture?

- What containers are available for storing water, mixing up a solution and measuring

salt, sugar and water ?

Your survey could also include the local shops, pharmacies and the nearest dispensaries

and health centres. At these places check:

- Which diarrhoea treatments are used.

- How much stock is kept and the turnover.

- Availability of packets of oral rehydration salts (ORS).

- If alternatives are used what do they cost and what is their chemical composition?

It is also important to examine water sources, storage of water and the use and

maintenance of sanitation. Summary of the important steps in a diarrhoea survey:

- Consider the questions that will provide the necessary information to improve the

diarrhoea service.

- Set these out in a questionnaire and test them with and on local people.

- Choose and train questioners.

- Survey a representative number of people in the community.

- Summarize the results and apply them to modify and improve the diarrhoea prevention and

treatment services.

Useful further reading: Barker DJT 1976 Practical Epidemiology. Oxford University Press. Bennett F J 1979

Community Diagnosis and Health Action. The Macmillan Press Ltd. Cutting W A M et al 1981 A worldwide survey on the treatment of diarrhoeal disease

by oral rehydration in 1979. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics 1: 4:199-208. McCusker J 1978 Epidemiology in Community Health. African Medical and Research

Foundation, Nairobi, Kenya. Werner D, Bower B 1982 Helping Health Workers Learn. The Hesperian Foundation,

Hesperian Foundation, 1919 Addison St., #304, Berkeley, CA 94704, USA,

1-510-845-1447 -

[email protected] -

www.hesperian.org

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 9 May 1982  7

Page 8 7

Page 8

DD in Sierra Leone

At a recent course sponsored by WHO in Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria, I had the opportunity to

be introduced to your publication Diarrhoea Dialogue. Could you kindly send me

regular supplies? I am a public health inspector and visit many training centres for

primary health volunteers here. I also give a lot of health talks during my routine

exercises particularly on the subject of diarrhoea. S. T. John-Sawaneh, Health Superintendent I/T, PMO/PHC Buildings, P.M.B. 439,

Makeni, via Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Information exchange We have in Brasilia a very well organized medical assistance. We have one health centre

for each 30,000 inhabitants for primary health care. And we carry on a very large

programme to eradicate diarrhoea and dehydration. So, as Director of the Community Health,

I am very interested to receive all you can send to me on primary health care about

diarrhoea, including Diarrhoea Dialogue. I will send you frequently our observations on our work here to exchange experiences. Professor Ernesto Silva, Director of Community Health, HRAS, QL 06 - Conjunto 11 -

Casa 2, S.H.1 SUL, 71600 Brasilia, Brazil.

Comments on cholera I have just seen Diarrhoea Dialogue for the first time and like it very much. I

think that the 'Clinician's Guide to Aetiology' in="dd07.htm">issue seven is

very useful, but I would not stress abdominal pain as a common feature in cholera.

Obviously patients do sometimes complain of abdominal pains but most do not

according to my experience here in Beira where I am responsible for a small cholera ward

with 20 beds.

|

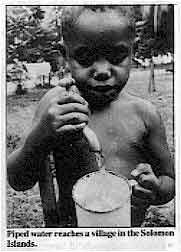

Piped

water reaches a village in the Solomon' Islands.

This year we have had around 100 confirmed cases of cholera in Beira - less than last

year. In many cases, oral rehydration therapy is sufficient treatment. In the more serious

cases, it is only in the initial stages that intravenous therapy is required. After that,

they too can receive fluids by mouth. I think that we should all demand the Nobel Prize in

Medicine for those behind the promotion of oral rehydration therapy using sugar-salt

solution! Dr Anders Hernborg, CP 2180, Beira, Mozambique.

|

|

Papua New Guinea

I am a Rural Health Nursing Sister of Gumine Kundiawa Simbu, Papua New Guinea. The use

of ORS has helped a lot of patients in wards and on home visits where I am. I have found

it very easy to use ORS, rather than telling parents to make "sugar wara" or any

other rehydration solution. I consider that ORS is very effective and arousing great interest in rural areas. Mui Henry, Rural Health Nursing Sister, Division of Health, Rural Health Centre,

Gumine, Chimbu Prov., Papua New Guinea.

Teaching aids In="dd07.htm">November 1981 issue of Diarrhoea Dialogue

you

gave a very comprehensive table - a 'Clinician's Guide to Aetiology' of diarrhoea. I

thought it was a very useful tool. I would really think that, in future, using this format

would be a great idea.

I would like to make a suggestion - if it was possible to get teaching slides or

pictures of the various types of diarrhoea stools, which can help in diagnosis, it would

be very helpful. I am involved in conducting training workshops for second tier health

personnel to upgrade their diagnostic and therapeutic skills.

I feel that more 'need-based' teaching aids for medical auxiliaries for their clinical

work are required, since these training programmes have to incorporate a lot in a short

while. 'Carry home practical advice' like the one in Diarrhoea Dialogue can be very

valuable.

Could you send a few extra copies, if possible, so that I can send it to others in the

field who are also involved in low cost health care at the grass roots.

Dr Mira Shiva, Voluntary Health Association of India (VHAI), C-14 Community Centre,

Safdarjung Development Area, New Delhi 110016, India.

Editors' note:

If you would like to receive a bulk supply of Diarrhoea Dialogue to distribute

locally, please state exactly how, many copies you would like. We can handle orders of up

to 200 copies for distribution through the normal postal system.

It would help us to make faster and more efficient alterations to the mailing list

if, when advising any change or addition, you could enclose an old label, advise your code

number, or state which country you were in for the previous mailing.

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Executive editor Denise Ayres Editorial advisory group

Professor David Candy (UK)

Dr I Dogramaci (Turkey)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr D Mahalanabis (India)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Mujibur Rahaman (Bangladesh)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Dr Paul Vesin (France)

Dr M K Were (Kenya) With support from WHO and UNDP

|

Issue no. 9 May 1982

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 April, 2014

updated: 23 April, 2014

|